Common Themes in Religion and the Essential Unity of All Religions

So many religions, so many paths to reach the same goal. I have practiced Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and in Hinduism again, the ways of the different sects. I have found that it is the same God towards whom all are directing their steps, though along different paths. -Swami Ramakrishna, Hindu Monk

Different Religions and Personal Beliefs

My parents celebrated my tenth birthday in an unusual way. Rather than showering gifts on me, my mother took me with her to feed the poor people outside the temples of six different faiths: a Sikh temple, a Hindu temple, a Jain temple, a Christian church, a Jewish synagogue, and an Islamic mosque. As I handed over two pieces of bread and some very appetizing curry to each person, I did not see Muslim or Hindu or Christian faces — I only saw grateful human faces. Even though it was a fleeting exchange — a small act of kindness and the acknowledgment of gratitude — I can still vividly remember the deep human connection I felt that day, and the profound sense of joy it gave me.

When we returned home, my father read from the scriptures of these six major faiths. He told us that there is only one God who has been manifested on Earth in different times through Krishna, Christ, Mohammed, Moses, Guru Nanak, Buddha, Mahavir, and many others. The words, Ekam sat vipra bahuda vadanti (truth is one, but called differently by many) from the Rig Veda (I.164.46) still ring in my ears. He ended our prayer by saying, Sarve Janah sukinoh bhavantu, (May ALL the peoples of the world be peaceful and prosperous).

Essential Unity of All Religions and Personal Beliefs

A few years later, I was reading a book given to me by my father. It was written by Dr. Radhakrishnan, a former president of India who also inaugurated the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School. In the book, Radhakrishnan wrote about how he recognized himself as an heir to the entirety of human civilization and not just Hindu civilization. This struck a chord within me that continues to resonate in my life today.

These two events, two beautiful gifts handed to me by my mother and father, enriched my life immeasurably by teaching me how to cherish and harness the diversity in the world around me.

Common Themes in World Religions and Personal Beliefs

My own family was Hindu, and this shaped the way I saw the world as I was growing up in Old Delhi. Hinduism came with its own set of beliefs and rituals, but ultimately, the emphasis was to find truth through one’s own experiences. I started my life as a believer, but at the same time, a seeker of truth.

My beliefs continued to evolve as I gained wider exposure to the world and became more analytical while pursuing an engineering degree. A lot of cognitive dissonance started to set in regarding the beliefs I held. However, as my beliefs continued to evolve, I still found value in religion. The difference was that I started to see religions not as a matter of absolute certainty or the “Word of God,” but more of a never-ending quest for meaning and truth. Viewed in this way, it becomes clear that much of religion is meant to be interpreted metaphorically rather than literally. This, in turn, makes it easier to find wisdom in all religions, without seeing them as conflicting with one another. Rather, they are all part of a shared human meaning-making project that has been ongoing for our entire history as a species. Of course, it took time for all of this to fully crystallize in my mind.

Interfaith Dialogue and the Essential Unity of All Religions

Hindus believe in four stages of life— Brahamcharya (discipline), Grahastha (pleasure), Vanaprastha (learning), and Sanyasa (retirement). Though I was not fully conscious of this at the time, it was my own personal pursuit of the third stage, Vanaprastha, that brought me to study at Harvard in the Advanced Leadership Initiative (ALI) program.

The ALI fellowship provided me with an amazing platform that allowed me to audit classes across the university without any grades or assignments — the perfect setting for my Vanaprastha stage of life. I did this not for any kind of certificate or other end result, but simply because I believe in learning as an autotelic activity — that it is valuable and fulfilling as an end unto itself!

I took a variety of classes on religions, including several on Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism. I thereby learned a lot about other faiths, as well as a lot about my own faith that I did not know. One of my key insights was that much of what I had believed in as literal truth from the Hindu scriptures was actually best interpreted metaphorically. I used to believe, for instance, that God incarnated on Earth as Krishna and actually gave a sermon in the form of the Bhagavad Gita. Now I believe instead that the Gita does contain profound wisdom, but it was given to us in the form of a fictional story so as to be more easily grasped by the average person. My new perspective on the Gita was catalyzed by a class I took with Professor Francis X. Clooney, who is a scholar of Hinduism as well as an ordained Jesuit priest. He told me that reading other religions helped him become a better Christian. This warm embrace of wisdom from diverse belief systems is a great model for the rest of us to follow. He exemplifies a type of religiosity that can be great for society and humanity, as being more authentically religious means showing true and unconditional love towards every “other.”

What is Interfaith Dialogue in the Context of World Religions?

Another eye-opening moment for me at Harvard came through a class on religion and world politics that I took in 2015 with Brian Hehir, a professor and MacArthur Fellow. It was in this class that I came to learn about the amount of violence in the world that has been committed in the name of religion. The role of politics in religion became evident to me, and I was convinced that all religious people must understand what role political forces have played in the history of their religions. Particularly appalling to me was the prevalence throughout history of intra-religious warfare. I couldn’t believe that millions of Catholic and Protestant Christians would slaughter each other over such minor religious differences when it was clear that both sides ultimately believed in and worshiped the same God — a God whose primary commands concern loving one another and even loving one’s enemy. The same can be said of Sunni and Shia Muslims. They share the same God and prophet, and yet they massacre each other. The violence of extreme forms of Islam is inimical to Mohammed’s teachings and in contravention of the teachings of Islam. Religious extremism and violence today are by no means confined solely to Islam. In India, even today, the higher castes continue to treat members of lower castes in despicable ways, despite legislation that has attempted to formally abolish the caste system. This occurs in spite of the shared religious belief that we all possess the same deeper essence of being (atman), and are therefore all fundamentally equal. This is not unlike the situation of racism in America, which has come under the national spotlight recently due to the black lives matter movement and the series of nationwide protests and demonstrations, which are a reaction to the fact that civil rights legislation of the past has not been enough to eradicate hate from people’s hearts. I contrasted all this with my childhood and asked, “How did this come about?”

Common Themes in All Religions and Personal Beliefs

I have many Hindu friends whose children have married Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Sikhs, and Jews — they never saw anything wrong with this, nor did I. So why do so many people see their faiths as incompatible and at odds with other faiths? How do we come to believe what we believe? Why aren’t we allowed to choose our religion? In most cases, our parents tell us what religion we should pursue.

The same can be said for politics, too. We inherit most of what we believe simply through the circumstances of our birth, and we are constantly taking the words of fallible human beings to be the ultimate truth. As Filmmaker Raoul Martinez notes, what we need is “a potent antidote to the worst excesses of arbitrary identification; to the sorts of narrow, entrenched, dogmatic worldviews that drive us to kill and die for flags, symbols, gods, and governments whose connection to us is no more than accidental.” Put in the language of our present-day circumstances, in the midst of a once-in-a-lifetime deadly pandemic, there is another virus that has corrupted our hearts and minds. Its symptoms include prejudice based on race, rank, region, various “isms,” bigotry, extremist forms of religion, and other related social problems. In a broader sense, these are all manifestations of the problem of “me vs. the other.” So long as a critical mass of us remain unvaccinated against the virus causing this problem, we will not have a healthy society, and we will not be able to fully flourish as a species. It was these sentiments that led me to found a new nonprofit institute, Universal Enlightenment & Flourishing, of which I am still the active director.

Common Themes in World Religions and the Essential Unity of All Religions

I decided to take what I learned in my classes at Harvard on religions, as well as my other classes in psychology, sociology, philosophy, and evolutionary biology, to share my experiences and learning of the deeply common nature and destiny that we share. I see UEF as working toward the development of a vaccine against the insidious virus that prevents us from extending unconditional love toward one another. One of the first big projects of Universal Enlightenment & Flourishing has been the writing of a book on commonalities across all religions. My goal was to write a book that would broaden and deepen our understanding of religions, demonstrate that religions have historical roots situated in distinct contexts, and help to change readers’ exclusivist views of religion. It dawned on me that many others might be able to benefit from a more critical examination, just as I have. Most of us do not have enough understanding of our own religions, much less those of others. This is only natural, as we are not taught about religions in grade school — at least not from a critical perspective — and most of us do not have the free time in our adult lives to pursue this kind of study on our own. There is simply too much religious literature out there to comb through! Until now. The beauty of this book would be to curate a collection of quotes and insights from the world’s major religions, distilling the main substance of human wisdom into a single concentrated product. When I worked at Unilever earlier in my career, the active ingredient in the soaps and other products we sold only constituted 5% of the total volume of the container! I think of this book project as a distillation of just that 5% of material from belief systems that will have the most powerful effect upon readers.

Common Themes in All Religions and Interfaith Dialogue

My connection to Harvard enabled me to gather a small team of researchers and writers to help me with this book, as well as other UEF projects. Among them is Allen, who graduated from Harvard Divinity School with a master of Theological Studies degree in 2018, and has been working on the religion book since then. He was very skeptical at first, wondering what the value of such a book would be among all the other existing literature on religions. Soon, however, he came to see the uniqueness of my approach and became more passionate about the project. This further convinced me that this would be a book that many readers would find to be powerful and important.

Early on in the research process, we were both surprised to learn just how many common themes we found across all religions — more than fifty! These similarities that we found are amazing from one point of view, but completely unsurprising if we view religion as a meaning-making endeavor of humanity that manifests itself in different contexts. In other words, although real differences across belief systems exist, they exist primarily due to historical and geographical context, as compared to the most important and prominent tenets of religions, which do not change across time and place — loving one’s neighbor, for instance. In a healthier world, religion would be viewed not as a competition over who is right and who is wrong, but rather a collective human endeavor toward meaning-making. Our differences should be seen as complementary aspects to be shared with one another in our collective quest as human beings to better understand the world we inhabit and our relationship to it. Because we all experience this same world in different ways, we only get closer to the truth by pooling our different perspectives.

Essential Unity of All Religions and Interfaith Dialogue

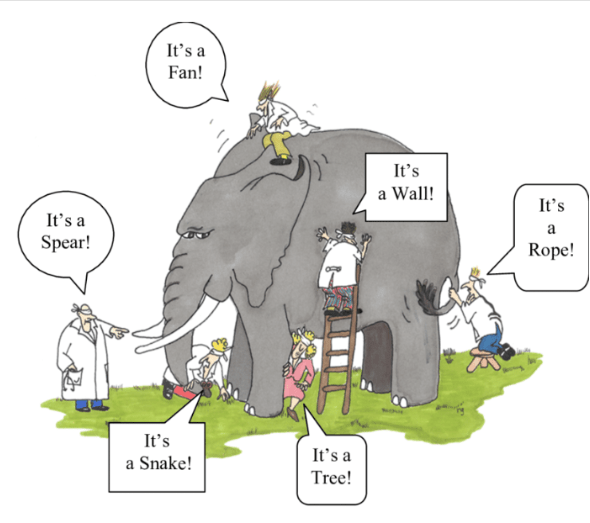

There is a well-known story in Indian religious texts, including those of Hinduism and Buddhism, about an elephant and a group of blind men. Because they are blind, the men must rely on their sense of touch to examine the elephant. Since they all are touching different parts of the animal — the trunk, the tail, the tusks, etc. — they all come to very different conclusions as to the identity of what they’re touching. Thus, the elephant can only be seen for what it is by the blind men if they each share and piece together their findings. This is how we should understand religion: each of the major prophets was dealing with limited information and resources based on their historical and geographical contexts. Furthermore, their insights had to be constrained in ways that would be communicable to their own people, rather than the people of other continents to which they were unable to travel. Nevertheless, their teachings all contain truths about humanity and the universe, and if we pool together these different, smaller truths today, we collectively would be closer to the bigger Truth. We want to help people love and celebrate the beautiful diversity that exists among us, and see this diversity as an opportunity rather than a threat. As Joseph Campbell once noted, “A single song is being inflected through all the colorations of the human choir.”

Common Themes in Religion and Interfaith Dialogue

After more than two years of conducting research for our book, we are ready to start sharing some of the beautiful quotes and insights we’ve gathered from the world’s major wisdom traditions. We welcome you to read the articles in this series, each of which will treat one of the common themes we have identified. But this is only the beginning. My nonprofit institute, Universal Enlightenment & Flourishing, is about more than just writing books on religions and other belief systems. These books are a starting point to lay the intellectual foundation of our mission. We are ambitiously starting a movement that we are hopeful will have a huge impact on the world. There are plenty of great educational institutions and resources out there. What we are trying to facilitate instead is a different type of learning, the enlightenment that comes from waking up, asking big questions about yourselves and the world around us, examining what we have been socially programmed to believe, and making the conscious decision to let go of all beliefs that hinder us from extending universal love to all others.

Popular Reads

Fire as a Symbol | Religious Wear | False Narrative | Chariot | Cosmic Tree | Sacred Words | Sacred Music | Allegory of The Cave | The Great Flood | Creation Story | Hippocratic Oath | Fasting and Religion | Spiritual Transcendence | Religious Texts | What Is Divine Justice | Higher Power | Gods Laugh | Spirituality and Money | Oneness with God | Religious Conversion | Religious Ritual | Sacred Spaces | Promised Land | Oneness with God | Kneel Before God |Divine Light |Rosary Beads | Tithing | The Golden Rule In All Religions | Sacred Words