Key Points:

Repetition carries significant value, anchoring our understanding and actions. Just as physical training builds muscle memory, our brains are trained through repeated thoughts and phrases. Religions often use daily recitations, like mantras, which serve as guiding points in life. These mantras, when repeated, can alter our neural pathways, even when we don’t fully grasp their meaning. For instance, Jews recite the Shema Yisrael daily to affirm the Oneness of God, while Muslims have their daily prayers and Quranic passages. Followers of Baha’i faith praise God by reciting ‘Allah’u’Abha’ 95 times a day, and Confucianism emphasizes memorization and repetition in education. In Indian religions, ‘Om’ signifies oneness and is frequently used as a greeting. Sikhs say ‘Wahe Guru,’ and Transcendental Meditation uses unique mantras to quiet the mind. Mantras have the power to shape our thoughts and actions, fostering a more enlightened and loving self through repetition.

On a day-to-day basis, we are all making our best efforts toward what Harvard University professor and psychologist Robert Kegan calls “meaning-making.” In his book The Evolving Self (1982), he puts into perspective how fundamental the concept of meaning-making is in terms of how we interact with the world: “it is not that a person makes meaning,” he writes, “as much as that the activity of being a person is the activity of meaning-making.” All religions have been born out of humanity’s efforts to make meaning about the world as we encounter it.

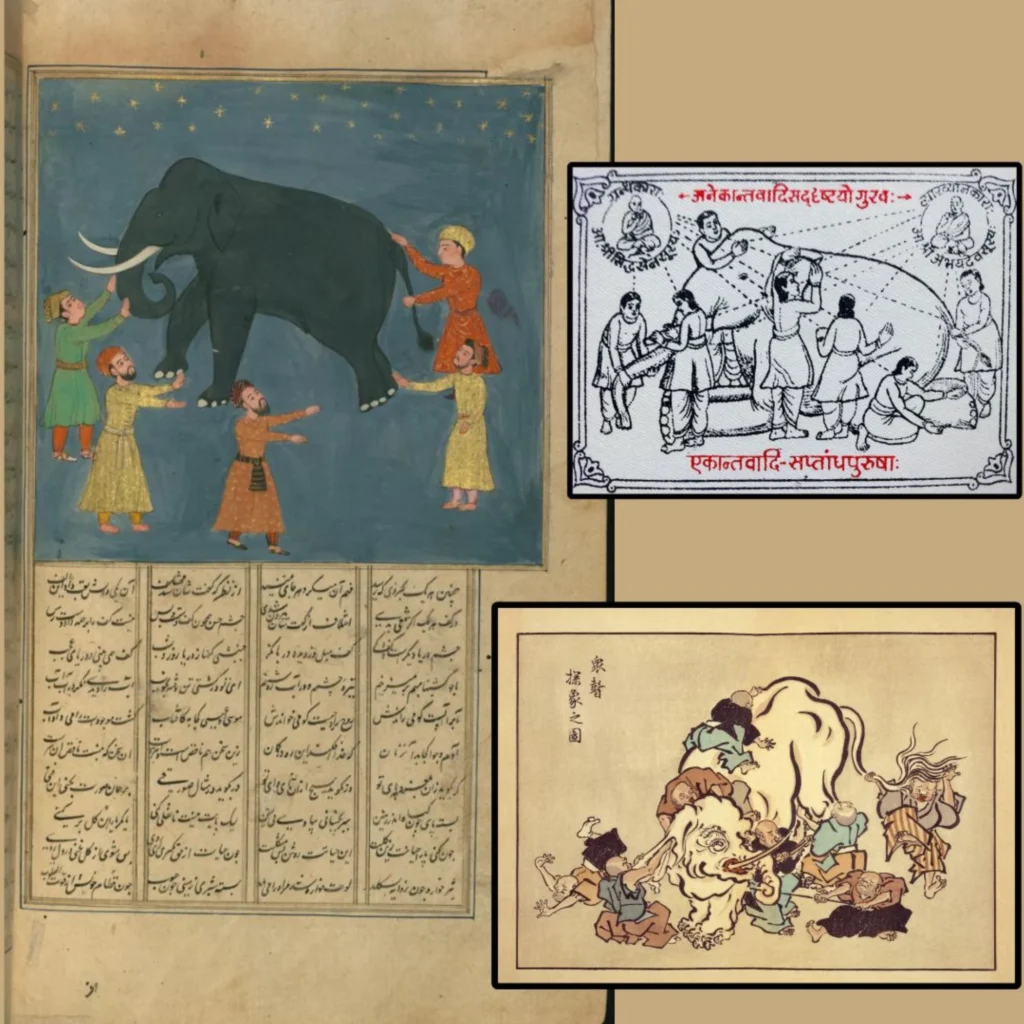

Picture a scene in which several curious people surround a large, gray elephant. Now imagine each person is absolutely blind. Each, having tentatively touched the part of the elephant standing before them—its wrinkled trunk, its vast and coarsely grained flank, its tree bark textured leg, its spindly tail, and large leathery ear—reaches a differing impression of the identity of this mysterious and unseen creature before them.

This is an oft-recounted parable originating in the Indian subcontinent and subsequently found in various texts across ancient wisdom traditions. It is meant to illustrate how we, as finite beings, can only partially grasp the true nature of something as grand as God or the universe.

Our universe is far too vast and mysterious for any of us individually to arrive at a comprehensively “true” understanding of its identity. The nature of God is too mysterious, too incomprehensible, and too ineffable for any one religion to describe in full, though each religion expresses its own valuable perspective of a larger truth.The diversity of beliefs we see across humanity do not indicate that some of us are “right” and everyone else is “wrong.”

I have come to view all religions, belief systems, and fields of study throughout history as so many responses to the shared human need to make meaning from the complexity and mystery of the world around us. The diversity we see in religions is a result of different contexts, differences at the individual level, and the ever-evolving nature of our knowledge of the world around us.

We will cover this in the next newsletter to show how a proper understanding of diversity in meaning-making is the true antidote to religious intolerance that we so desperately need right now.

“My Hindu instinct tells me that all religions are more or less true. All proceed from the same God, but all are imperfect because they have come down to us through imperfect human instrumentality.”

– Gandhi, acknowledged as Father of the Nation by Indians

“I believe all religions pursue the same goals, that of cultivating human goodness and bringing happiness to all human beings. Though the means might appear different, the ends are the same.”

— His Holiness The Dalai Lama, Tibetan Buddhist leader

“To me, religions are like languages: no language is true or false; all languages are of human origin; each language reflects and shapes the civilization that speaks it.”

— Rabbi Rami Shapiro, Jewish author and teacher