Key Points:

The key message is that meaning-making is a deeply personal and cultural process, resulting in a wide spectrum of interpretations and beliefs. The text encourages tolerance and appreciation for the rich diversity of meaning-making approaches across different faiths and traditions. It suggests that recognizing these differences as complementary rather than conflicting can promote understanding and unity among people of diverse backgrounds, ultimately contributing to a more enlightened and harmonious global society. In essence, it underscores the importance of celebrating and respecting the various paths that humanity takes on its quest for meaning, just as we savor the diversity of cuisines from different cultures to satisfy our physical hunger.

The Bible recounts that Jesus taught the same lesson to different people in different ways, adjusting to each audience’s familiarity with the concepts or receptivity to allegorical illustration. Indeed, Jesus told his followers, ‘To you is given the mystery of God’s Kingdom, but to those who are outside, all things are done in parables.’ (Mark 4:11) Similarly, the Buddha tutored his most devoted monks in more direct and explicit terms than he did the larger masses, who had to be taught through ‘skillful means,’ or parables that simplified truths or insights in ways that would be more digestible to an audience of mixed levels of education and knowledge about the world.

People make meaning differently according to differing levels of complexity, resulting from the differences in upbringing, historical context, educational opportunities, and other such factors. Psychologist Robert Kegan refers to these differing levels of complexity as “orders of mind” in his book, In Over Our Heads (1994).

At any given time in history, some people will be able to foster meaningful connections to God through very literal interpretations of religious stories, rituals, and so forth. Others will crave more symbolic ways of meaning-making because they process the world in general through a more complex order of mind. This does not mean one person is “right” and the other “wrong”–they are simply making meaning in different ways.

This happens across history as well. There are certainly some beliefs and practices that seem foolish or barbaric to us today, but which were valid and important ways of making meaning many years ago. Meaning-making itself is universal, but the ways in which people make meaning differ quite a bit.

That being said, it is encouraging to see how humanity’s collective meaning-making has been constantly evolving as literacy rates, access to education, and scientific knowledge have all improved.

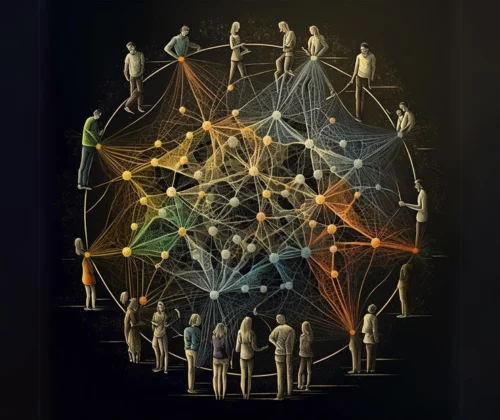

Individual differences in meaning-making will always exist, but if people from various faiths could understand their differences as complementary contributions toward a common quest (meaning-making), rather than toward a common creed, then we could eliminate so much fear, hatred, and violence in the world. We would also become more enlightened as a species, with each of us being able to bring together the wisdom from all religious traditions and belief systems.

When we feel hungry, most of us enjoy satisfying that hunger by eating foods from a wide variety of different cultures. Each type of cuisine is designed to deliver the same essential nutrients, but still we feel enriched by indulging in meals from different cultures.

Similarly, I am impressed by all the similarities I see across religions regarding the questions we ask to satisfy our hunger for meaning. The answers, while different in many ways, still arise out of the common human quest toward meaning-making and represent a diversity that can and should be savored by all.

“Each religious genius spells out the mystery of God according to his own endowment, personal, racial, and historical. The variety of the pictures of God is easily intelligible when we realize that religious experience is psychologically mediated.”

– Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, philosopher and former President of India

“We should continually try to broaden the circle of our acquaintances, associate with those who are of different religion, race and nationality, and by this means come to a fuller understanding and appreciation of one another.”

— Abdu’l-Bahá, Baha’i prophet

“The great man shows his greatness by combining all the common aspects of humanity. So, when ideas come to him from outside, he can receive them but does not cling to them. Likewise, when he brings forth some idea from within himself, they are like guides to those around but they do not seek to dominate.”

— The Book of Chuang Tzu, Taoist text